For more information, contact:

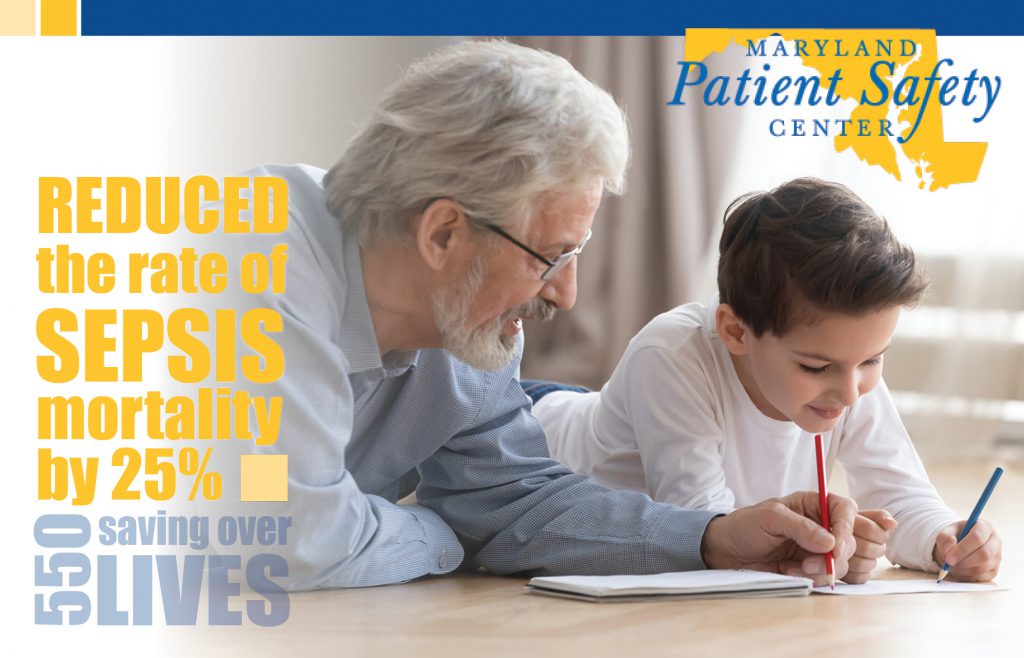

Improving Sepsis Survival

Maryland Patient Safety Center (MPSC) and Maryland Hospital Association (MHA) partnered to lead an initiative to reduce sepsis mortality in Maryland hospitals. Sepsis occurs when an infection, such as pneumonia, triggers a cascading, whole-body inflammatory response that, if left untreated, can rapidly lead to progressive organ failure and death. In addition, sepsis is among the top 10 most common potentially preventable complications across Maryland hospitals, and one of the leading causes of mortality and readmission.

MPSC and MHA worked together to create opportunities for hospital staff to convene in-person and virtually to learn from and share with experts and each other about the prevention and treatment of sepsis. These meetings included information on early recognition and assessment processes, standardized treatment, and coordinated communication to help with patient flow between the emergency department and other areas of the hospital.

WEBINARS

The Road to the Sepsis Inpatient Quality Measures: Are We There Yet? (08/11/2015)

Hospital participants in Cohort 1 of the Improving Sepsis Survival Initiative:

Carroll Hospital Center

Frederick Regional Health System

Garrett County Memorial Hospital

Holy Cross Hospital

The Johns Hopkins Hospital

MedStar Montgomery Medical Center

Meritus Medical Center

Northwest Hospital

Sinai Hospital of Baltimore

University of Maryland Baltimore Washington Medical Center

Hospital participants in Cohort 2 of the Improving Sepsis Survival Initiative:

Bon Secours Baltimore Health System

Calvert Memorial Hospital

Howard County General Hospital

Laurel Regional Hospital

MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center

MedStar St. Mary’s Hospital

MedStar Southern Maryland Hospital Center

Shady Grove Medical Center

Suburban Hospital

Washington Adventist Hospital

Western Maryland Health System

Maryland hospitals take aim at costly, deadly sepsis

By: Daniel Leaderman Daily Record Business Writer June 29, 2015

It’s one of the deadliest and most expensive conditions a patient can face, but a campaign is underway to help Maryland hospitals detect symptoms of sepsis early so they can save more lives.

“This involves a cultural shift within hospitals,” said Robert Imhoff, president and CEO of the nonprofit Maryland Patient Safety Center. “It’s a new way of doing things.”

Imhoff’s organization has teamed up with the Maryland Hospital Association to help 21 hospitals in the state develop procedures to detect sepsis early.

These procedures require coordinated teams of doctors, nurses, pharmacists and phlebotomists to spring into action quickly; an hour’s delay could mean the difference between life and death, said Bonnie DiPietro, the center’s director of operations.

Some steps, such as drawing blood and administering antibiotics, need to occur within 3 hours of detecting sepsis; others, such as giving drugs to raise the patient’s blood pressure, must be done within six hours, she said.

Sepsis doesn’t have a single cause. It occurs when the body experiences widespread inflammation due to an infection. It causes damage to the body’s organs, which can lead to organ failure and even death, DiPietro said.

On average, about 30 percent of those who develop severe sepsis or septic shock will die, and the condition claims about 1,100 lives in Maryland each year, she said.

A report from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality found that in 2011, sepsis was the most expensive condition treated in the nation’s hospitals, accounting for 5.3 percent, or $20.3 billion, of national hospitalization costs that year. Other recent studies indicate that treatment for sepsis can cost a patient as much as $50,000.

Sepsis is one of 65 “potentially-preventable complications” that Maryland hospitals are tasked with reducing under the terms of the state’s new global-budget model, which caps hospital revenue as an incentive to reduce preventable illness and hospital readmission.

The safety center’s initiative, just beginning its second and final year, is based on a program begun at the University of Maryland Charles Regional Medical Center in La Plata in 2012, Imhoff said.

After noticing a rising number of sepsis cases, the hospital began asking patients with symptoms of infection a series of questions when they first enter the emergency room, said Dr. Richard Ferraro, chief of the medical staff at Charles Regional and chair of the hospital’s emergency department.

If a patient also has abnormal vital signs, the nurse will issue a “code sepsis” alert, prompting an immediate response from the medical team: the patient will be given fluids, antibiotics and an assortment of diagnostic tests, Ferraro said.

“It sounds simple, but for years and years we were not getting it right,” he said. “We were missing the opportunity to intervene early.”

Since the medical team needed to respond to a “code sepsis” was already on staff, there was really no additional cost to the medical system; and since sepsis treatment in an intensive-care unit can cost thousands of dollars a day, a few hundred dollars worth of tests early on made financial sense, Ferarro said.

For many patients, a “code sepsis” turn out not to be septic once further tests are run, Ferarro said. But while such “high-sensitivity” procedures sometimes yield false positives, doctors are catching all sepsis cases, he said.

From 2010 to the first half of 2013, the sepsis survival rate at Charles Regional increased from 79.7 percent to 89.5 percent, according to data from the hospital.

In January of 2014, the rest of the hospitals in the University of Maryland Medical System began implementing similar sepsis-response procedures, Ferarro said.

And six months later, the 10 hospitals in the first cohort of the patient-safety center’s initiative began developing their own procedures; the second, 11-hospital cohort began in April, said DiPietro.

While it was too early to provide meaningful data on the results — some of the participating hospitals had to make more changes under the initiative than others, depending on their existing procedures — there was a “decreasing trend” in incidents of advanced sepsis, DiPietro said.

“Not all sepsis is preventable,” she said. “[But] we do know that early detection can reduce mortality.”